In our previous installment of Simcident Report, we took a close look at the post-9/11 flight sim world, ranging from the reactions of simmers, to the bizarre wave of moral outrage surrounding the hobby from the outside. In the end, for all of the supposed controversy, the simming hobby as a whole suffered little if anything in the way of real consequences. Unfortunately, this wasn’t true for everyone…

Welcome to Simcident Report, where we take a look at noteworthy, dramatic, and historic events in flight simming. Today, we will examine the bizarre stories of how the post-9/11 surveillance state got the police sent to the home of a 10-year-old boy and landed another man in US federal court, all over accusations of little more than being fans of flight sim.

Heroic Staples Employee Foils Terrorist Plot by 10-Year-Old Boy and His Mother

About a week before Christmas in 2003, Colrain Massachusetts resident Julie Olearcek, a 15-year Air Force Reserve pilot, entered a Staples store to search for flight instruction software for her 10-year-old son. The son was interested in learning instrument procedures and wanted to be a pilot like his parents. Olearcek was expecting an uneventful Christmas shopping trip but instead found herself accused of aiding and abetting terrorists by retail employees.

Olearcek would describe the bizarre experience to her local newspaper, “[My son] was disappointed because there was military stuff, but it was all fighting stuff, so I asked the clerk, and he was alarmed by us asking how to fly airplanes and said that was against the law. I said I couldn’t imagine that, but, because (the clerk) was a little on edge… so I left.”

That night, Olearcek and her family would receive a frightening visit from a Massachusetts State Trooper asking if they had inquired about flight training software.

Sgt. Donald Charpentier of the Shelburne Falls State Police Barracks would tell Recorder.com, that he had gotten a telephone call from the Staples manager “that a person had been looking for instructional videos regarding flying planes. Those programs are quite common for entertainment and training, but we felt it was suspicious enough to warrant a call.”

Staples spokesperson Sharyn Frankel would state that the employees were doing what they had been told to do. “After 9/11, our store associates were instructed that if they see something suspicious or out of the ordinary, they’re to contact their managers and local authorities. It’s all about keeping our associates and customers safe and this was out of the ordinary and kind of raised a red flag and they did what they thought was right.”

(Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

After some brief questioning the Massachusetts State Police were able to determine that Olearcek and her 10-year-old son were not budding terrorist masterminds and they were released without further incident. Olearcek would say of her experience “At first, I felt a little angry and violated, But now that time has gone by, I realize it may take someone like that, who’s a little nervous, who may save the day.”

If You See Something Say Something… Even if You Didn’t See Anything

Now, nearly 20 years later, it’s easy to dismiss basically everybody involved in this incident as a paranoid lunatic, but we need to look at this in the context of post-9/11 America. It really is impossible to overemphasize the unease and fear that average Americans felt in the aftermath of the events of September 11th. The idea that the average citizen needed to employ constant vigilance in the face of seemingly endless terrorist threats became ingrained in American society, largely due to a number of public awareness campaigns with catchy slogans such as the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority’s (MTA) now infamous “If You See Something, Say Something.” After the campaign launched in December of 2002, reports of suspicious packages in New York grew from 814 in 2002 to 37,614 in 2006. The slogan was subsequently licensed and adopted by government agencies around the country including the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

(Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

While these campaigns undoubtedly increased public awareness of terrorist threats, it’s much more difficult to say how effective these programs have been at stopping actual terrorist plots. According to a 2008 report by the New York Times, of the thousands of reports made to the state’s anti-terrorism hotline between 2006-2008, only 18 led to arrests and none of those were related to any potential terrorist plots.

Indeed, many reports of suspicious activity made to various government hotlines in the years following 9/11 were the result of paranoid misunderstandings or outright fabrications. Fortunately, in the instance of Olearcek and her son, everyone came away weirdly understanding of what happened and nobody suffered any lasting consequences.

Unfortunately, this would not be the case for every alleged flight simmer who would be swept up by the American security apparatus.

Suspicious Male Subject in Possession of Flight Simulator Game

In May of 2012, police officers arrived at the home of Chico, California resident Wiley Gill to investigate a report of domestic violence. Gill, a devout Muslim, was home alone. The domestic violence suspect the police were looking for was not and had never been in his house.

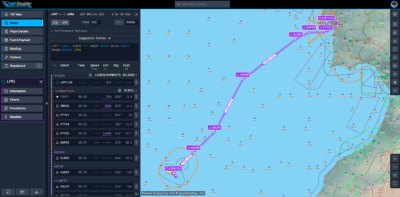

The police searched the residence and found Gill had a “flight simulator type of game” on his computer. Gill disputes the police account, saying that he was simply reading about games online in an article titled something like “Games that Fly Under the Radar.” In either case, officers found Gill’s behavior suspicious enough to warrant the creation of a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR), entering Gill into a federal government database of suspicious activity that could be related to terrorism.

The Nationwide SAR Initiative (NSI) was created in 2010, around the same time that the DHS adopted the New York MTA’s “If you see something, say something” slogan. The program is intended to provide a framework of information-sharing for local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies with regards to potential terrorist activity. The program was an evolution of the various information-sharing practices put into place after 9/11 by state and federal agencies.

The SAR filed for Gill, entitled Suspicious male in possession of flight simulator game details Gill’s traditional Islamic garb and long beard, unemployment, as well as his history of being evasive around law enforcement, before going into his apparent interest in flight simulators.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) took the Department of Justice (DOJ) to court in 2014 on behalf of Gill and four other plaintiffs who had dubious SARs filed against them for various innocuous activities including photographing an industrial park, looking at exits in a train station, and buying large numbers of computers.

The ACLU argued that the standards applied to SARs submitted to the National Suspicious Activity Reporting Initiative were too broad and didn’t necessarily need to include reasonable suspicion of a crime being committed. They challenged the SAR based on a procedural rule of the Administrative Procedure Act which stated that any legislative rule enacted by a federal agency was subject to a public comment period. The ACLU argued that since the SAR program had not undergone this public comment period it was not a legal program. They would also argue that the standards applied to these reports were “arbitrary and capricious” because there was no requirement for “reasonable suspicion” that a crime was being committed.

Indeed, the method by which SARs were processed and shared by law enforcement agencies was a byzantine and little-understood process. The Washington Post would report in 2010 that the cost and scope of the intelligence gathering programs developed by the United States Government were difficult to impossible to gauge. One estimate would point to at least $31 billion in grants given to local and state agencies between 2003 and 2010 to improve information gathering and processing. Much of this information would be forwarded to so-called “fusion centers” to be analyzed with further details gathered and added to cases where necessary.

The case Gill v. DOJ, went to trial and was eventually sent up to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. The 9th Circuit Court would ultimately rule in 2019 in favor of the Department of Justice. The court held that the SAR program was not a legislative rule because it required “significant analyst discretion” and therefore was exempt from the public comment period. Essentially, the court ruled that since the SARs were processed according to a series of guidelines and not hard requirements it didn’t meet the criteria of being a legislative rule.

The program was also held by the court not to be “arbitrary and capricious” because the guidelines for information-sharing were well-defined and consistent with the goals of the mission of the Information-Sharing Environment, and the subjects of the database were not being charged with crimes. Ultimately this means that anybody can be subject to an SAR for flight simming (or any other reason) at the discretion of some anonymous analyst and entered into a government terrorism database, but this is ok because you aren’t actually being accused of anything, the government is just keeping an eye on you.

Once again, it’s difficult to say how effective this program has been. Opinions vary with some experts citing that the volume of information gathered is too vast and makes for an inefficient use of law enforcement resources. Others within the DOJ however, point to the various cases in which this Information-Sharing Environment has led to arrests. The program remains controversial with critics pointing to the scope creep and ill-defined mission while the fusion centers themselves have been categorized as a government “no mans land” sitting between sate and federal agencies with no clear path for authority or accountability.

Flight Simming is Not A Crime

The above incidents demonstrate just how far-reaching the effects of the September 11th attacks have been on American life. Once again, we can view the flight sim world as a microcosm of the larger post-9/11 world with pervasive surveillance and the gradual erosion of civil liberties taking center stage. Perhaps the most ironic twist is that neither the younger Olearcek nor Gill were even confirmed to be flight simmers themselves. All it took was a paranoid individual to think that they were, that this activity was somehow suspicious, and report them to authorities.

While, globally, the threat of terrorism from all manner of extremist groups undoubtedly remains a very real problem, it’s certainly disappointing to think that actions as simple as buying a copy of Microsoft Flight Simulator from Staples or browsing gaming websites could be enough to gain you a visit from the police or get you entered into a federal database. In a world where “If you see something, say something” has become a guiding principle for the average citizen, fear and paranoia are the new normal.

I’m on a watch list now right?

Feel free to join our Discord server to share your feedback on the article, screenshots from your flights or just chat with the rest of the team and the community. Click here to join the server.